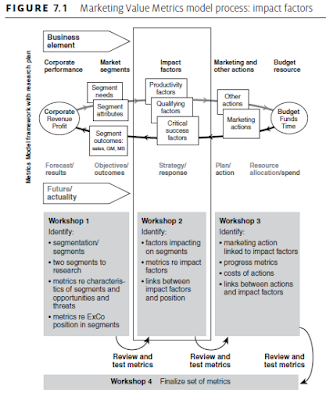

The position of this stage of the overall model is shown in Figure 7.1. This is a critically important step in the process described in thi...

The position of this stage of the overall model is shown in Figure 7.1. This is a critically important step in the process described in this book, so it requires quite a lot of discussion and explanation. Metrics identified here are at the heart of the overall measurement strategy. The results from this analysis help address the view expressed at the start of this chapter, as it proves the rationale for allocating resources to marketing.

1 qualifying factors;

2 critical success factors;

3 productivity factors.

The templates needed to undertake an analysis for each set of factors are shown, including examples. As shown in Figure 7.2, the objective of the analysis described in this chapter is to identify the impact factors for each market segment that the organization wants to focus on.

The key characteristics of qualifying factors are:

● They need to be at a minimum level.

● They only differentiate negatively.

● Improving performance for these factors does not create competitive advantage.

Qualifying factors are all about not losing out to competitors or being disadvantaged in a market. They are essential to maintaining the current position relative to other players in a market. As such they do not provide any differentiation from others operating in a market or confer any competitive advantage.

A simple example of a qualifying factor might be the logistics requirement specified by a supermarket for suppliers delivering to a central distribution depot. The supermarket specifies next-day delivery following receipt of an order to its five regional warehouses. The key account manager for this customer at Supplier A established that with some additional investment it would become possible for them to make same-day deliveries to the customer for any order placed up to 5 pm. The account manager believed that their competitors would not be easily able to match this level of service. However, discussions with the customer identified the reason for specifying a next-day service. This requirement was based on the need to plan each evening for the flow of deliveries scheduled for the following day in order to maximize the unloading capacity of the warehouse, ensure that delivery truck queuing time was kept to a minimum and balance incoming delivery capacity with the need to have sufficient outgoing slots for vehicles delivering to its stores. Therefore, being able to offer a faster service was ascertained as being of no value to the customer. However, the conversation clearly underlined that being unable to guarantee a next-day delivery service would rule a supplier out of contention – this was the qualifying service level required for all suppliers to this customer.

● the list of all the qualifying factors that are essential to operating effectively in this segment of the market;

● the metrics that will be necessary to measuring whether or not the organization is meeting the requirements of the market;

● the methods that will be used to derive or obtain the measures, for example the source of the metric, or the data from which it will be derived;

● the importance of each factor relative to the others, to help assess priorities for actions, which is based on a percentage applied to each factor, adding up to 100 per cent;

● an assessment of current performance – what the organization is achieving at present against the performance expected in the market;

● the performance level necessary, if the organization is currently under- or over-performing, against market expectations;

● the current performance expected by those in this segment of the market.

The template (Table 7.1) includes an example for a catalogue clothing company to illustrate how the cells might be completed. The market segment shown for the clothing company in Table 7.1 is described as ‘stylish urbanites’. Market research and competitive intelligence have identified three key factors that are required to meet customers’ basic expectations: customer orders are accurately recorded, phones are quickly answered, and prices are in line with those of competitors. The company has therefore set targets for all three to bring its performance into line with the performance of other companies serving this sector. For example, the company has

decided that the metric for measuring the accuracy of order taking is the number of products returned where the customer states as the reason that the goods were not what was ordered. The current level of returns for this reason is 20 per cent, compared to 3–6 per cent for competitors. The target is set at 5 per cent, as this is in line with the performance of others and the expectation of customers.

How do qualifying factors become established in a market? At the beginning of this chapter a brief example was described for a key account customer covering deliveries to a supermarket. A further example, from the financial services sector, provides an illustration for consumer markets. Some years ago a leading UK high street bank advertised that customer service calls would be answered in six rings. By promoting this through imaginative television commercials, in addition to establishing an initial advantage over competitors, they established in consumers’ minds an expectation for all these types of calls, to any organization. In addition, consumer research also established that consumers did not want phone calls to be answered in a shorter time, as they needed a breathing space between dialling and connecting to an agent to prepare themselves mentally for the conversation to come. Therefore there was no incentive for organizations to invest in additional resources in order to answer calls any faster. Six rings became at that time the qualifying factor for customer service calls. The metric is obvious, and the measurement process would be found in the elapsed time between a call arriving in the centre and being answered, or through mystery shopping.

Obviously, while such practices may enable budgets to be met in terms of agent resources and productivity targets, consumers will eventually recognize that this organization does not meet their expectations and, if this is an important factor for them, they will transfer their business to a competitor.

Organizations would be ill advised to invest resources in improving performance above the qualifying level if customers do not care, or do not want improved performance, as illustrated by the supermarket example described earlier in the blog.

Examples where organizations fail to attain qualifying levels include those with customer service websites that provide no other method to contact the organization, and contact centres being unable to deal immediately with common enquires at the time of a call or not having up-to-date information about the customer available to support the conversation.

To be successful, in addition to understanding the needs of consumers, a company must also monitor the activities and performance of key competitors, and be tuned into changing circumstances. The important point to bear in mind when identifying CSFs and performance levels is that the perspective must be that of consumers and their needs and expectations – not what an organization might want to offer or think might be acceptable and not based on what competitors are doing.

Undertaking a SWOT analysis, helps identify how the organization stands up against the needs of consumers and competitors. Market research is obviously another vital source of consumer understanding, and inspiration for developing innovative solutions to meet needs. For example, market research conducted on a regular basis among customers that are new to a company may identify issues of importance to consumers that are not being adequately met by competitors.

Issues to consider in identifying CSFs are:

● Demand from consumers, or needs (fulfilled and unfulfilled): Sometimes market research establishes a common need across a market, but by breaking the analysis down by segment, one can identify differences that can be exploited to make your offer appeal more versus competitors to a target segment. An illustration of this is from the car breakdown service market. Research identified that drivers who were competent mechanics wanted a service that delivered their broken-down vehicle to their home so they could repair it for themselves, rather than being towed to the nearest garage. This led to the thought that there might be a demand for a more flexible service from other types of car owners. Further research proved this to be the case, leading to the very successful development of an optional service that took the car to a destination of the driver’s choice (eg the driver’s home, local dealer or garage) and provided a replacement car either for the completion of the journey or until the driver could make other arrangements if the repair was going to take time.

● Importance to the customer: Organizations need to ensure that they can prioritize the needs of consumers in order to ensure they focus on those that matter most. The opportunities for differentiation can then be identified by analysing the performance of competitors against their own for each need. This might also identify where a competitor is over-achieving against the requirements of customers, and therefore squandering its scarce resources. Undertaking a critical success factor analysis is one way to identify what really matters to consumers and whether there are any opportunities that can be exploited to deliver competitive advantage. This is also a tool that could be used in market research focus groups. As Jeremy Bullmore comments in his book Apples, Insights and Mad Inventors (2006): ‘We all have invisible maps in our heads, on which we plot the position of competing brands. Every brand is allocated to its own, unique space. There may or may not be such things as parity products; there are certainly

no parity brands.’

● Level required by consumers, and how a company matches these expectations: This is a further extension of the critical success factor analysis. For example, if customers require a quicker delivery service, what precisely does this mean and what degree of latitude is the customer prepared to tolerate? Are consumers wanting a faster service, and are they prepared to pay extra for it (eg the different delivery options offered by Amazon)?

● The company’s performance relative to that of key competitors: The important issue here is to see competitors through the eyes of consumers. Do not rely on the perspective taken of competitors by the organization itself.

● Perceptions of consumers: Consumers do not necessarily interpret the messages from organizations in the way intended. Often they do not read the small print. They also have their own individual prejudices and see what they want to see. So-called ‘irrational’ cognitive processes are the focus of the popular field of Behavioural Economics but can be said to really be underpinned by the Nobel prize winners Kahneman and Tversky (1972, 2012). New messages do not necessarily replace, or erase, experiences from the past. Take brand image as an example. Organizations claim to own brands but, turning again to Jeremy Bullmore (2006), he reminds us: ‘But for a company to feel it owns its brands is to tempt it to believe that it has total control over them: and it does not.’ Bullmore continues: ‘Forget the marketing-speak. The image of a brand is no more nor less than the result of its fame: its reputation. And like a reputation, it can be found in only one place: in the minds of people.’ When the Automobile Association introduced its Relay service in the UK to recover members’ cars (and occupants) to their home or local garage, the name was deliberately chosen, as on a recovery journey of any length the car and occupants might be transferred at operational area boundaries to other vehicles, just as a baton is passed from one runner to another in a relay race. However, some members missed this connotation, or didn’t read how the service operated, and were therefore surprised to find that their journey was not completed in one stage. Their perception was that this would always be the case. Organizations have to decide how to deal with consumers’ perceptions – but the key point is to know they exist, and how they are developed, if effective action to try to correct them is to be taken.

● Identifying opportunities where excellence has potential leverage with customers: In some cases it may be possible to make changes to a product formulation, or how a service is delivered, that provides customers with a level of benefit out of all proportion to the investment. The added advantage here is that this drives word-of-mouth marketing – the impact of customers speaking so positively about an organization that it persuades their friends and relatives to try out the brand. The level of customer service provided by First Direct in the financial services sector and the level provided by Zen Internet Ltd in the broadband market are prime examples where excellence has driven advocacy.

CSFs are all about winning through differentiation against key competitors. The winning strategies are born out of an in-depth understanding of consumers and their needs – and the creative ability to turn this knowledge into innovatory solutions. Taking the call centre example described earlier in the chapter, how could customer service centres create competitive advantage if answering calls faster wasn’t a worthwhile solution? The answer lay in the quality of the conversations with customers, which in turn relates to the training of the agents, the processes that support them, the attitude of management, and the objectives and metrics set for the call centre by senior management. Market research was used to identify what consumers defined as excellent customer service over the phone, collecting examples from consumers

covering a wide range of organizations operating in different market sectors.

Elements of best practice that consumers wanted included:

● quickly answered (the qualifying factor level);

● 24/7 service;

● a pleasant greeting;

● professional service;

● confidence in the process;

● providing a name and reference number;

● customer details and history to hand.

The research also indicated that the benchmark organizations were First Direct (banking services) and Direct Line (car, home and contents insurance), both of which at the time had business models based on providing their services via the phone.

If the core metrics for the call centre focused on the productivity of the agents, then it was unlikely that the service could be differentiated from that of competitors. (In fact, a focus on productivity can lead to customers being ill served, for example by paying agents a bonus based simply on the number of calls answered in a defined time period. This was the strategy adopted by the directory enquiry service 118 118 when it was initially launched, with callers sometimes being given incorrect numbers simply to enable the call to be quickly ended so that the targets of calls handled could be achieved.)

The solution was to develop a scorecard of metrics that include measures reflecting the needs and expectations of customers, the conversational skills of agents, and their ability to handle a range of queries and offer appropriate additional products and services, in addition to metrics measuring productivity. The main measurement processes might include ‘mystery shopping’ surveys to measure responses by agents against defined criteria, and customer satisfaction market research, together with call centre system statistics such as the level of abandoned calls.

Over time, the competitive advantage factors of today may become the qualifying factors of the future. As in the call centre example, any initial market advantage gained from telling consumers that ‘Our phones are answered in six rings’ as a competitive advantage factor could in fact be readily matched over time by competitors as they saw that this was creating an expectation among key customers. This does not mean that the factor has diminished in importance; it has simply become the expected norm in the market, and other factors need to be identified if an organization is to gain competitive advantage.

● a description of each CSF (eg fastest available service);

● the metric that can measure performance (eg meeting a four-day service delivery target);

● where this performance is measured (eg production and logistics reports);

● the importance to customers relative to other factors (eg a weighting of 40);

● what the current level of performance is (eg eight days);

● what the realistic target might be, and when this can be achieved by (eg the four-day target will take two years to achieve fully);

● what the current benchmark is (eg the best performer in the market provides service in six days).

● reducing inefficiencies, or eliminating wasteful activities: restructuring the sales force to focus on key accounts with a call centre or website to serve the needs of lower-value customers;

● process improvement and alignment: decreasing the time from order placing to when the product reaches the customer by using web-based technology and restructuring the logistics operation;

● restructuring: replacing product-based teams with account teams;

● matching channel to segment preference: ensuring that a range of channels is available to meet the needs of different customer types and provide service capabilities outside normal working hours cost-effectively;

● pipeline, or value chain, effectiveness: using tools such as Porter’s value chain analysis, as described below, to identify strengths and weaknesses in the organization’s overall capability to serve customers as efficiently as possible.

● Customer service effectiveness: Customer management processes and systems, particularly online channels, allow companies to reduce the cost to serve while improving customer experience in some instances.

The following case study illustrates how a leading UK engineering company has added value and reduced costs by developing a new web-based facility for customers. The measures used to assess the outcomes are also described.

While the initial web store development was not subject to a detailed justification, the subsequent business cases were primarily based on reducing the average cost of order processing, plus measuring:

What are impact factors?

Impact factors are divided into three types:1 qualifying factors;

2 critical success factors;

3 productivity factors.

The templates needed to undertake an analysis for each set of factors are shown, including examples. As shown in Figure 7.2, the objective of the analysis described in this chapter is to identify the impact factors for each market segment that the organization wants to focus on.

Qualifying factors

Qualifying factors are those factors, and associated levels of performance, that all organizations operating in a market are expected to deliver from a customer’s perspective. Unless a company can provide these at the level expected by customers it is unlikely to prosper in the market.The key characteristics of qualifying factors are:

● They need to be at a minimum level.

● They only differentiate negatively.

● Improving performance for these factors does not create competitive advantage.

Qualifying factors are all about not losing out to competitors or being disadvantaged in a market. They are essential to maintaining the current position relative to other players in a market. As such they do not provide any differentiation from others operating in a market or confer any competitive advantage.

A simple example of a qualifying factor might be the logistics requirement specified by a supermarket for suppliers delivering to a central distribution depot. The supermarket specifies next-day delivery following receipt of an order to its five regional warehouses. The key account manager for this customer at Supplier A established that with some additional investment it would become possible for them to make same-day deliveries to the customer for any order placed up to 5 pm. The account manager believed that their competitors would not be easily able to match this level of service. However, discussions with the customer identified the reason for specifying a next-day service. This requirement was based on the need to plan each evening for the flow of deliveries scheduled for the following day in order to maximize the unloading capacity of the warehouse, ensure that delivery truck queuing time was kept to a minimum and balance incoming delivery capacity with the need to have sufficient outgoing slots for vehicles delivering to its stores. Therefore, being able to offer a faster service was ascertained as being of no value to the customer. However, the conversation clearly underlined that being unable to guarantee a next-day delivery service would rule a supplier out of contention – this was the qualifying service level required for all suppliers to this customer.

Qualifying factors template

The template shown in Table 7.1 is for listing the qualifying factors for each segment in the market and the information needed to identify the appropriate metrics strategy for each one. The necessary content comprises:● the list of all the qualifying factors that are essential to operating effectively in this segment of the market;

● the metrics that will be necessary to measuring whether or not the organization is meeting the requirements of the market;

● the methods that will be used to derive or obtain the measures, for example the source of the metric, or the data from which it will be derived;

● the importance of each factor relative to the others, to help assess priorities for actions, which is based on a percentage applied to each factor, adding up to 100 per cent;

● an assessment of current performance – what the organization is achieving at present against the performance expected in the market;

● the performance level necessary, if the organization is currently under- or over-performing, against market expectations;

● the current performance expected by those in this segment of the market.

The template (Table 7.1) includes an example for a catalogue clothing company to illustrate how the cells might be completed. The market segment shown for the clothing company in Table 7.1 is described as ‘stylish urbanites’. Market research and competitive intelligence have identified three key factors that are required to meet customers’ basic expectations: customer orders are accurately recorded, phones are quickly answered, and prices are in line with those of competitors. The company has therefore set targets for all three to bring its performance into line with the performance of other companies serving this sector. For example, the company has

decided that the metric for measuring the accuracy of order taking is the number of products returned where the customer states as the reason that the goods were not what was ordered. The current level of returns for this reason is 20 per cent, compared to 3–6 per cent for competitors. The target is set at 5 per cent, as this is in line with the performance of others and the expectation of customers.

How do qualifying factors become established in a market? At the beginning of this chapter a brief example was described for a key account customer covering deliveries to a supermarket. A further example, from the financial services sector, provides an illustration for consumer markets. Some years ago a leading UK high street bank advertised that customer service calls would be answered in six rings. By promoting this through imaginative television commercials, in addition to establishing an initial advantage over competitors, they established in consumers’ minds an expectation for all these types of calls, to any organization. In addition, consumer research also established that consumers did not want phone calls to be answered in a shorter time, as they needed a breathing space between dialling and connecting to an agent to prepare themselves mentally for the conversation to come. Therefore there was no incentive for organizations to invest in additional resources in order to answer calls any faster. Six rings became at that time the qualifying factor for customer service calls. The metric is obvious, and the measurement process would be found in the elapsed time between a call arriving in the centre and being answered, or through mystery shopping.

Obviously, while such practices may enable budgets to be met in terms of agent resources and productivity targets, consumers will eventually recognize that this organization does not meet their expectations and, if this is an important factor for them, they will transfer their business to a competitor.

Organizations would be ill advised to invest resources in improving performance above the qualifying level if customers do not care, or do not want improved performance, as illustrated by the supermarket example described earlier in the blog.

Examples where organizations fail to attain qualifying levels include those with customer service websites that provide no other method to contact the organization, and contact centres being unable to deal immediately with common enquires at the time of a call or not having up-to-date information about the customer available to support the conversation.

Critical success factors (CSFs)

These are the factors that really matter to consumers in a market, or segment. They focus on important customer needs: hence the alternative name ‘competitive success factors’. These are the factors that attract attention in the market and help an organization win, and retain, customers. Focusing on improving performance against these creates positive, and powerful, advantage over competitors. Improving performance against these factors should lead to increased market share. However, there is likely to be a lag effect between improving performance and a noticeable impact on market share, and this needs to be allowed for in plans, cash flow forecasts and metrics.To be successful, in addition to understanding the needs of consumers, a company must also monitor the activities and performance of key competitors, and be tuned into changing circumstances. The important point to bear in mind when identifying CSFs and performance levels is that the perspective must be that of consumers and their needs and expectations – not what an organization might want to offer or think might be acceptable and not based on what competitors are doing.

Undertaking a SWOT analysis, helps identify how the organization stands up against the needs of consumers and competitors. Market research is obviously another vital source of consumer understanding, and inspiration for developing innovative solutions to meet needs. For example, market research conducted on a regular basis among customers that are new to a company may identify issues of importance to consumers that are not being adequately met by competitors.

Issues to consider in identifying CSFs are:

● Demand from consumers, or needs (fulfilled and unfulfilled): Sometimes market research establishes a common need across a market, but by breaking the analysis down by segment, one can identify differences that can be exploited to make your offer appeal more versus competitors to a target segment. An illustration of this is from the car breakdown service market. Research identified that drivers who were competent mechanics wanted a service that delivered their broken-down vehicle to their home so they could repair it for themselves, rather than being towed to the nearest garage. This led to the thought that there might be a demand for a more flexible service from other types of car owners. Further research proved this to be the case, leading to the very successful development of an optional service that took the car to a destination of the driver’s choice (eg the driver’s home, local dealer or garage) and provided a replacement car either for the completion of the journey or until the driver could make other arrangements if the repair was going to take time.

● Importance to the customer: Organizations need to ensure that they can prioritize the needs of consumers in order to ensure they focus on those that matter most. The opportunities for differentiation can then be identified by analysing the performance of competitors against their own for each need. This might also identify where a competitor is over-achieving against the requirements of customers, and therefore squandering its scarce resources. Undertaking a critical success factor analysis is one way to identify what really matters to consumers and whether there are any opportunities that can be exploited to deliver competitive advantage. This is also a tool that could be used in market research focus groups. As Jeremy Bullmore comments in his book Apples, Insights and Mad Inventors (2006): ‘We all have invisible maps in our heads, on which we plot the position of competing brands. Every brand is allocated to its own, unique space. There may or may not be such things as parity products; there are certainly

no parity brands.’

● Level required by consumers, and how a company matches these expectations: This is a further extension of the critical success factor analysis. For example, if customers require a quicker delivery service, what precisely does this mean and what degree of latitude is the customer prepared to tolerate? Are consumers wanting a faster service, and are they prepared to pay extra for it (eg the different delivery options offered by Amazon)?

● The company’s performance relative to that of key competitors: The important issue here is to see competitors through the eyes of consumers. Do not rely on the perspective taken of competitors by the organization itself.

● Perceptions of consumers: Consumers do not necessarily interpret the messages from organizations in the way intended. Often they do not read the small print. They also have their own individual prejudices and see what they want to see. So-called ‘irrational’ cognitive processes are the focus of the popular field of Behavioural Economics but can be said to really be underpinned by the Nobel prize winners Kahneman and Tversky (1972, 2012). New messages do not necessarily replace, or erase, experiences from the past. Take brand image as an example. Organizations claim to own brands but, turning again to Jeremy Bullmore (2006), he reminds us: ‘But for a company to feel it owns its brands is to tempt it to believe that it has total control over them: and it does not.’ Bullmore continues: ‘Forget the marketing-speak. The image of a brand is no more nor less than the result of its fame: its reputation. And like a reputation, it can be found in only one place: in the minds of people.’ When the Automobile Association introduced its Relay service in the UK to recover members’ cars (and occupants) to their home or local garage, the name was deliberately chosen, as on a recovery journey of any length the car and occupants might be transferred at operational area boundaries to other vehicles, just as a baton is passed from one runner to another in a relay race. However, some members missed this connotation, or didn’t read how the service operated, and were therefore surprised to find that their journey was not completed in one stage. Their perception was that this would always be the case. Organizations have to decide how to deal with consumers’ perceptions – but the key point is to know they exist, and how they are developed, if effective action to try to correct them is to be taken.

● Identifying opportunities where excellence has potential leverage with customers: In some cases it may be possible to make changes to a product formulation, or how a service is delivered, that provides customers with a level of benefit out of all proportion to the investment. The added advantage here is that this drives word-of-mouth marketing – the impact of customers speaking so positively about an organization that it persuades their friends and relatives to try out the brand. The level of customer service provided by First Direct in the financial services sector and the level provided by Zen Internet Ltd in the broadband market are prime examples where excellence has driven advocacy.

CSFs are all about winning through differentiation against key competitors. The winning strategies are born out of an in-depth understanding of consumers and their needs – and the creative ability to turn this knowledge into innovatory solutions. Taking the call centre example described earlier in the chapter, how could customer service centres create competitive advantage if answering calls faster wasn’t a worthwhile solution? The answer lay in the quality of the conversations with customers, which in turn relates to the training of the agents, the processes that support them, the attitude of management, and the objectives and metrics set for the call centre by senior management. Market research was used to identify what consumers defined as excellent customer service over the phone, collecting examples from consumers

covering a wide range of organizations operating in different market sectors.

Elements of best practice that consumers wanted included:

● quickly answered (the qualifying factor level);

● 24/7 service;

● a pleasant greeting;

● professional service;

● confidence in the process;

● providing a name and reference number;

● customer details and history to hand.

The research also indicated that the benchmark organizations were First Direct (banking services) and Direct Line (car, home and contents insurance), both of which at the time had business models based on providing their services via the phone.

If the core metrics for the call centre focused on the productivity of the agents, then it was unlikely that the service could be differentiated from that of competitors. (In fact, a focus on productivity can lead to customers being ill served, for example by paying agents a bonus based simply on the number of calls answered in a defined time period. This was the strategy adopted by the directory enquiry service 118 118 when it was initially launched, with callers sometimes being given incorrect numbers simply to enable the call to be quickly ended so that the targets of calls handled could be achieved.)

The solution was to develop a scorecard of metrics that include measures reflecting the needs and expectations of customers, the conversational skills of agents, and their ability to handle a range of queries and offer appropriate additional products and services, in addition to metrics measuring productivity. The main measurement processes might include ‘mystery shopping’ surveys to measure responses by agents against defined criteria, and customer satisfaction market research, together with call centre system statistics such as the level of abandoned calls.

Over time, the competitive advantage factors of today may become the qualifying factors of the future. As in the call centre example, any initial market advantage gained from telling consumers that ‘Our phones are answered in six rings’ as a competitive advantage factor could in fact be readily matched over time by competitors as they saw that this was creating an expectation among key customers. This does not mean that the factor has diminished in importance; it has simply become the expected norm in the market, and other factors need to be identified if an organization is to gain competitive advantage.

Critical success factors template

Table 7.2 shows the template for recording the CSFs analysis, illustrated by an example for the telecommunications industry for a segment based on small to medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) with an annual turnover (TO) less than £500,000. The analysis shows that a key factor creating differentiation would be a new service aimed at meeting the specific needs of companies in this segment, rather than continuing to provide services tailored to market sectors. As the template shows, there is a benchmark competitor (Competitor X) identified as offering a similar product to that planned, but with a lower performance than the market requires (measured through market research), which will need to be constantly monitored. The information needed to complete this template for the first CSF in Table 7.2 includes:● a description of each CSF (eg fastest available service);

● the metric that can measure performance (eg meeting a four-day service delivery target);

● where this performance is measured (eg production and logistics reports);

● the importance to customers relative to other factors (eg a weighting of 40);

● what the current level of performance is (eg eight days);

● what the realistic target might be, and when this can be achieved by (eg the four-day target will take two years to achieve fully);

● what the current benchmark is (eg the best performer in the market provides service in six days).

Productivity factors

While qualifying and competitive advantage factors are primarily about increasing market share, sales volumes and, in the case of CSFs, protecting or improving margins, productivity factors are about finding ways to create efficiencies and thereby improve profitability. Productivity factors enable the organization to become more efficient and focused in delivering the strategy for each segment. This can include increasing output, leveraging economies of scale and reducing the cost to serve each customer. Factors to consider when identifying productivity factors opportunities include:● reducing inefficiencies, or eliminating wasteful activities: restructuring the sales force to focus on key accounts with a call centre or website to serve the needs of lower-value customers;

● process improvement and alignment: decreasing the time from order placing to when the product reaches the customer by using web-based technology and restructuring the logistics operation;

● restructuring: replacing product-based teams with account teams;

● matching channel to segment preference: ensuring that a range of channels is available to meet the needs of different customer types and provide service capabilities outside normal working hours cost-effectively;

● pipeline, or value chain, effectiveness: using tools such as Porter’s value chain analysis, as described below, to identify strengths and weaknesses in the organization’s overall capability to serve customers as efficiently as possible.

● Customer service effectiveness: Customer management processes and systems, particularly online channels, allow companies to reduce the cost to serve while improving customer experience in some instances.

The following case study illustrates how a leading UK engineering company has added value and reduced costs by developing a new web-based facility for customers. The measures used to assess the outcomes are also described.

Case study

To facilitate online product ordering, a leading global engineering company developed an online offer that allowed customers to specify detailed sub-assemblies and customize fitting for components, submit the resulting specification, which CAD technology on the supplier’s server turns into a three-dimensional engineering drawing for the customer to view. The customer can then submit any amendments to the specification and input the final order into the system.

This process provided an added value, highly flexible service to the customer, saving time and the necessity of producing individual drawings of what is required. For the company, the automated CAD created a significant cost saving of £5 per drawing, or £2,500 per week based on the average weekly demand for 500 drawings. The site is supported by a 24/7 centralized multilingual customer service contact centre handling queries from phone calls or the website. Overall, the site attracted 24,000 visitors per week and generated 11 per cent of UK turnover for the company.

While the initial web store development was not subject to a detailed justification, the subsequent business cases were primarily based on reducing the average cost of order processing, plus measuring:

● overall levels of system usage (measured as ‘traffic’);

● the number of downloads;

● sales generated;

● the number of registrations.

● the number of downloads;

● sales generated;

● the number of registrations.

A further important measure is provided through a monthly report comparing benefits with

costs. (Mouncey, McDonald and Ryals, 2004)

costs. (Mouncey, McDonald and Ryals, 2004)

A key future development will be to expand the functionality of the site and develop strategies to maximize the opportunities for additional business from site visitors, especially from the large proportion who visit only the home/news or technical information pages. Of course, we can speculate that additive printing can take this co-creation process even further and allow the firm to sell the file that enables the production of sub-assemblies.

One mistake by marketers that Binet and Field (2007) highlight is that they can forget that the profit margin on incremental sales is normally higher than the average profit margin. Marketers, in building the case for investment, would be wrong to calculate margin at the increment if the activity requires more assets to meet additional demand. For example, filling empty seats on a scheduled airline incurs only a small additional cost and all incremental ticket sales go straight to the bottom line. Incremental production in a factory that has spare capacity enjoys high margin as there is no need to incur further overheads. However, a major increment in, for example, car sales that requires new plant and equipment, will enjoy ‘average’ margins

for that firm rather than the higher marginal rate.

for that firm rather than the higher marginal rate.

Using a value chain analysis to identify productivity factors

As mentioned above, one proven method that can help identify possible areas where efficiencies or improvements might be found is to undertake an analysis of the organization’s value chain, using a tool such as Porter’s (1980), as shown in Figure 7.3.

The objective of this commonly applied tool is to identify the strengths and weaknesses within the primary and support activities that contribute to delivering value to the market. The primary factors are the essence of what the organization does to serve customers and generate profits. Figure 7.4 illustrates an analysis of the primary value part of the chain for a manufacturer. As in all cases, the picture shown is a mixture of things the organization does well and some that are less good. The importance of these factors will depend on how they impact on meeting customer needs in different segments. It is vital that the analysis identifies the implications of each strength and weakness (‘This means that...’). For example, if the customers in a key segment set tight deadlines for orders being delivered, reliable production facilities are important, but of less importance in serving a group of customers who are less demanding in this respect. Similarly, the analysis suggests that once a customer gets through to speak to the call centre, the staff will quickly resolve the problem – unfortunately, this facility is often available only during a normal working day (UK time), and is closed at weekends. Again, this might be fine for UK customers, but not those in other time zones or those who are operating 24/7. It is also possible to compare an organization’s primary chain with known facts about those of key competitors. Figure 7.5 continues the value chain analysis for this manufacturer, for support activities. As with the primary activities, some strengths are shown, together with weaknesses. This is an organization that has invested heavily in technology, which should be delivering benefits, especially in terms of efficient procurement and e-auctions for commodities. The matrix structure should facilitate efficient decision making, especially as the organization appears to be able to recruit and retain professional staff. The reliance on a limited number of key suppliers could make the company vulnerable to price rises and shortages. Analysing the support activities also provides an understanding of the organization’s culture and its focus. Again, this profile can be compared with that of competitors.

for commodities. The matrix structure should facilitate efficient decision making, especially as the organization appears to be able to recruit and retain professional staff. The reliance on a limited number of key suppliers could make the company vulnerable to price rises and shortages. Analysing the support activities also provides an understanding of the organization’s culture and its focus. Again, this profile can be compared with that of competitors.

The focus in identifying productivity factors should be on those areas of the value chain where performance is significantly below that of competitors, or where internal factors are inhibiting the ability to meet consumer expectations. An example from an organization that one of the authors has worked with concerned the performance of the 250-strong sales team. A benchmark study revealed a high level of underperformance compared with the sales teams of rival organizations. A small budget for training quickly transformed the performance in terms of the number and quality of sales calls, which made a significant improvement in productivity. While this didn’t result in competitive advantage, it definitely avoided disadvantage in a very competitive market.

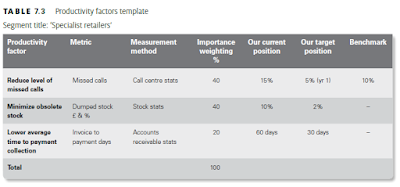

Productivity factors template

Table 7.3 shows the template for analysing the productivity factors. In this case a manufacturer is left with a high level of obsolete stock in its dealings with a segment defined as specialist retailers, mainly because the call centre is missing calls from customers in this segment. In addition, profitability is hit by an inefficient invoicing and payments process. The information needed to complete this template includes:

● a description of each productivity factor (eg reduce the level of missed calls);

● the metric that will measure performance (eg the volume of missed calls from customers);

● where the metric will be sourced (eg call centre statistics);

● the importance of each factor, relative to other factors (eg a weighting of 40);

● the current performance (eg 15 per cent of calls are missed);

● the target level of performance and when it can be achieved (eg 5 per cent achieved by the end of one year);

● the benchmark performance achieved by the best competitor (eg 10 per cent of calls missed).

Looking further at the call centre example shows that relevant solutions might be to look at less costly ways to deliver customer service, such as via a website that would also provide 24/7 service at lower cost than a call centre operation outside normal business hours, or outsourcing the call centre operation either to regions of the world where operating costs would be lower or to call centre outsource specialists.

COMMENTS